Did you know that birds can smell?

Maybe to you this seems like an obvious question; birds have noses, they must be able to smell. Or maybe you’re like me and genuinely never connected the idea of smelling and a strange, static bird beak. And, look, I grew up raising chickens, I’ve cleaned out my share of chicken coops on more than one occasion, and maybe it’s the frankly obscene level of stink that chickens produce that made me assume they must not be able to smell. Maybe it’s something in their affect. Chickens were the first birds I ever viewed up close or handled in any way, and while I have a healthy appreciation for the complexities of chicken problem solving and social behavior, I can confidently say that they are not the smartest animals. Chickens particularly have a kind of narrow, or perhaps specific intelligence, in which they are able to detect and hunt down a single snail in a compost pile, while simultaneously being unable to understand that shiny plastic objects are not, in fact, food. There something in this raptorish, ancient kind of thinking that implies, from my comfortable perch in the primate family with all my cerebral cortex and abstract thinking, an overreliance on visual queues. Then again “monkey see monkey do,” so who am I to judge.

All of this to say that for many years (perhaps an embarrassing amount of years, given my profession) I never considered the possibility that birds can smell. My surprise when I learned that not only can all birds smell, but that many hunt primarily by smell, was pretty severe.

But I was comforted to know that I was not exactly alone in my confusion. For many years the scientific community at large assumed, like me, that birds must not be able to smell well, if at all. In fact, the way we figured it out was a bit of a fluke.

In the 1930’s, Union Oil Company began rolling out large natural gas pipelines to bring energy to cities throughout America. You may not know this, but the “smell” of natural gas, that rotting eggs scent that tells you when you’ve left your stove on or your gas line is faulty, is not actually part of the gas. The scent comes from an additive, mercaptan, mixed with the gas to allow consumers to notice dangerous leaks. Technicians on the large gas pipelines began to notice that they could more easily find large leaks in the system by the flocks of vultures circling the damaged pipes, and realized that the vultures themselves were smelling the chemical additive and flocking to look for the meal it suggested was in the area.

This phenomenon was not well studied until the 1980’s when experiments were conducted exploring vultures’ ability to locate carcasses at various states of decay. This paper from 1986 explores the ability of two vulture species to find chicken carcasses, both concealed and unconcealed. It shows that vultures were equally able to locate food regardless of its visibility, and in fact were more effective at locating a meal the longer it had been left to rot. This makes sense, logically, as vultures are not just foraging in large open spaces (despite what western films may have you believe) but actually spend a large portion of their time in forested or riparian areas, and would therefore need to be able to find food that might not be visible from the air.

Much of the investigation of bird olfaction took place in the previous century. Experiments in vulture behavior, dissections of bird brains, anecdotal evidence of birds reacting to smells in their environment, all this may suggest a thorough understanding of how birds sense their world, but in reality there is a lot we don’t know about the topic.

For example, did you know that birds have whiskers? Yes, whiskers, like a house cat.

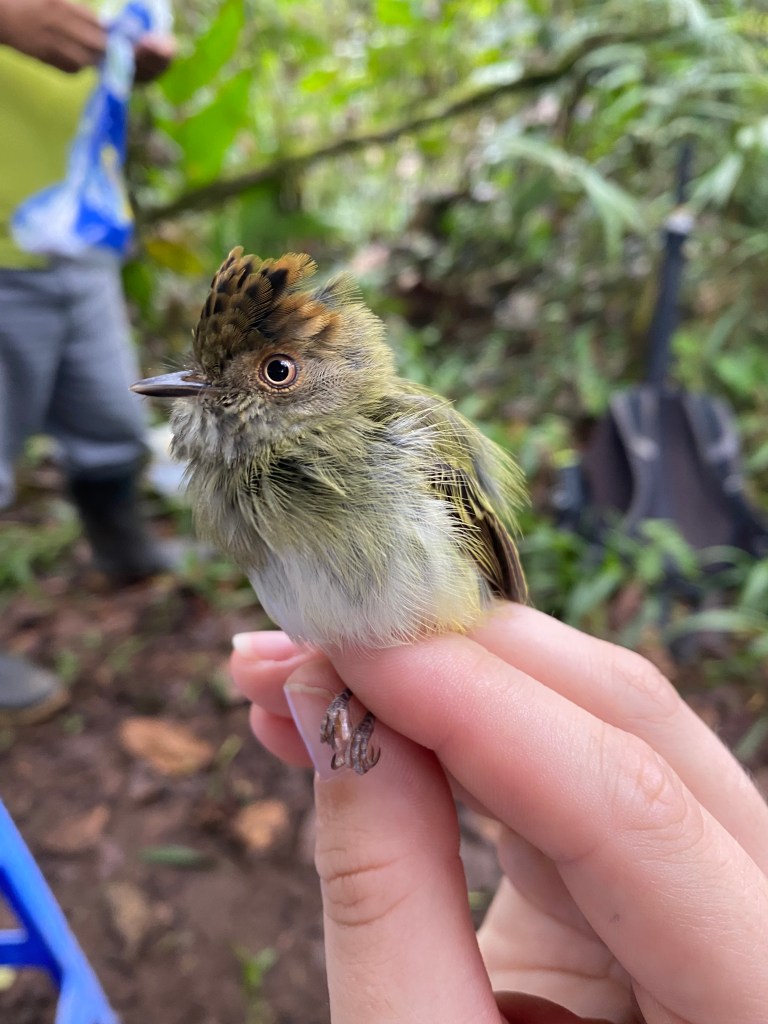

Check out the whiskers on this Tawny-breasted Flycatcher. I banded this bird in Ecuador in 2022, I was shocked when I handled it and realized how big its whiskers were!

Whiskers, or rictal bristles, are modified feather structures around a birds face and bill. Initially these were assumed to perform a mechanical function, and early ornithologists suggested that these whiskers might “scoop” insects into the bird’s open mouth. Later observational studies performed with high-speed photography showed that this was not the case, but the actual function of rictal bristles is still hotly debated. These modified feathers don’t appear to be monophyletic, meaning they don’t only appear in one lineage of birds, or in a certain group. In fact some phylogenetic studies suggest that whiskers may be an ancestral trait present as far back as saurischian dinosaurs. Structural studies show rictal bristles to be highly innervated, indicating they perform a sensory function, but field studies of their actual use are few and far between. Sensation is a difficult concept to study observationally, as we can only guess what is going on inside an animal’s head, and experimental studies on wild birds are generally strictly regulated for ethical reasons, so scientists can’t (rightly so) just go around cutting the whiskers off birds to see what happens. (As a child, one of my friends once cut the whiskers off her house cat when her parents weren’t looking. Turns out cats use their whiskers to sense the size of spaces to judge if they can fit into them, and I recall watching that poor thing get its head stuck in cabinets constantly.) But it’s a safe bet that rictal bristles are important, even if we don’t know how yet.

We do know that these feathers are found on a wide variety of birds, and seem to be especially well-developed in insect-eating species, suggesting they may play a roll in sensing the movement of prey. Perhaps whiskers sense sonic or electromagnetic changes in the air and help a bird to judge where its prey is while in flight, or perhaps they, like cat whiskers sensing the space around a cat’s head, tell the bird what the bug is doing just before the moment of impact, allowing them to adjust their beak for the perfect catch. Someday we will have studies to learn the true purpose of rictal bristles, whether they are an aspect of smell or touch or some secret third thing. Until then, personally, I just think they’re neat.

Here are a few more pictures of birds I’ve banded with prominent whiskers, and a few fruit-eating birds that seem to lack whiskers entirely, supporting the idea that their function is in prey capture. Enjoy!

This Red-eyed Vireo has much less noticeable whiskers than the flycatcher.

Some birds, like the Scale-crested Pygmy-tyrant, White-throated Spadebill, and Ochre-breasted Antpitta pictured, have easily visible whiskers, while some, like the Bay Wren in the last photo, are barely noticeable. Fruit eaters, like the tanager, the Red-Headed barbet, and the Club-winged Manakin don’t seem to have visible whiskers at all.

See you soon!

Leave a comment